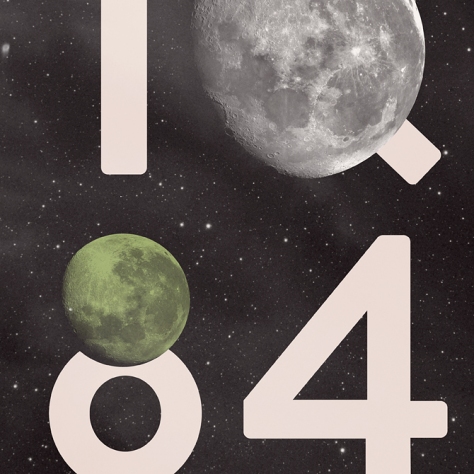

1Q84

Part II, Chapters 1-10

By Dennis Abrams

Aomame goes to see the Dowager and learns that the day after the guard dog explodes, Tusbasa has gone missing. The Dowager feels that the dog’s death triggered her disappearance (a message? a warning?) and is more convinced than ever that the Leader has to be sent to another world.

Aomame is told that after she kills the Leader, she will have to undergo plastic surgery and remove herself from her current life. The Dowager tells Aomame that she wishes that she was her own daughter; Aomame asks Tamaru if he can provide her with a gun – if she is captured during her mission, she plans to kill herself.

Aomame has now memorized every note of the “Sinfonietta” (we’ve also learned that it’s one of Tengo’s favorite pieces…) Tamaru calls Aomame to tell her he has found a new guard dog, and that her moon watching is beautiful (although she can’t muster the courage to ask him how many moons he sees.) He also tells her that she’ll have her gun the next day.

In the meantime, Aomame has begun to donate her books to charity and to give away her few books and other possessions. The Dowager reveals that she has planted a spy inside Sakigake, who has passed along the word that Aomame is an expert massager/muscle-stretcher. The Leader has health problems that he must keep hidden, so it is arranged that Aomame will visit him alone outside the compound, and although he travels with two bodyguards, there are no plans for them to be in the room when the time comes.

Tamaru gives Aomame a gun and teachers her how to us it, along with telling her how to quickly and properly kill herself if it becomes necessary. He also make sure that she’s prepared to travel or leave quickly if there’s a problem, and gives her a beeper in case he needs to get in touch with her. She later learns that Ayumi has been killed during a sexcapade with an unknown man.

Tamaru gives Aomame a gun, and shows her how to use it. He also tells her how to properly commit suicide on the spot, if needed. He also makes sure she’s prepared to travel or leave quickly if there is an issue and gives her a beeper in case he needs to get in touch with her. She later learns that Ayumi has been killed during a sex spree by an unknown man.

Aomame reacts to strongly to Ayumi’s death, realizing that her sexual needs were even wilder than her own, but the dangers caught up to her. Five days later, Tamaru pages Aomame and tells her to go to the lobby of the Hotel Okura’s main building.

She goes to Shinjuju station, where she rents a locker and places a small piece of luggage with enough money and clothes for several days inside. She realizes that this will be her last job: that the payoff will be big (she’ll be well provided for by the Dowager) but that the change of revenge from Sakigake is great. And while she knows that everything is about to change, memories of Tengo will always be with her.

At the hotel, Aomame has a sense of unreality, as though the hotel is a fantasy world of ghosts and vampires dressed in business suits and dresses. Two bodyguards, who she “names” Buzzcut and Ponytail meet her, look her over, and bring her to a room in the hotel where they search her. But, embarrassed, the guards don’t make her finish emptying out her purse, or check through her lingerie and personal items, where she has everything hidden. In the bathroom she changes, and checks over her gun.

Back in the room, the guards reveals that they have run a background check on her, and swear her to secrecy.

Buzzcut brings her into a very dark room where a large man is lying on the bed – he waked up and tells Buzzcut to leave; telling Aomame will not be harmed. The man is in his fifties with long hair; he refers to himself as the Leader and says that there are very few people who knows what he looks like. It seems that he suffers from bouts of muscular paralysis (during which his muscles and dick harden) for which there is no known cure. It is during this time that girls are brought to him to have sex, although he feels nothing in the process – it is all part of a religious practice so that girls will bear his children. The Leader also knows that he is headed for destruction, as each bout of paralysis is becoming progressively longer.

He tells Aomame that when he is finished, those who are causing the paralysis are eating away his flesh, but that it is the price he has to pay for some sort of heavenly grace. The Leader then tells Aomame to do what she always does.

And…Tengo…

Tengo writes, listening to Janacek’s Sinfonietta, and reads a newspaper detailing Fuka-Eri’s disappearance, which Tengo now knows is a publicity stunt.

At the cram school where Tengo teaches (our first visit there), an exceedingly ugly and strange man named Mr. Ushikawa comes to speak to Tengo. According to his business card, Ushikawa is from the New Japan Foundation for the Advancement of Scholarship and Arts, and organization that provides stipends for talented and creative people to pursue their work without having to make a living at a “regular” job at the same time. Tengo is told that he is under consideration for such a grant as an talented aspiring novelist (even though he hasn’t published much of anything). The source of the funding is somewhat mysterious, but Ushikawa hints that he knows that there is something going on between Tengo and Fuka-Eri, and that the press would certainly enjoy looking into it further. Komatsu believes that the Foundation has an ulterior motive for contacting Tengo (really?), the Professor though, is still out of touch and cannot be reached.

At the same that Aomame is thinking about Tengo, Tengo is thinking back on when he was ten, and the sensation he felt while holding her hand. He very much wants to see her again now that he is turning thirty. He thinks about the account of Jesus having his anointed with oil by the woman from Bethany before he dies. (Why?) He also begins writing a story about a world with two moons in the evening sky in the east.

Newspapers have begun reporting on Fuka-Eri’s past, on her family, and her disappearance (although no new details have emerged. Komatsu writes to Tengo (avoiding the phone for fear of a wiretap perhaps) including rave reviews of the book, as well as information about the Foundation. It does actually exist, it’s funding is unknown, and Komatsu suspects that Sakigake is involved.

Tuesday night, Tengo receives a phone call from Yasuda, who is the husband of Kyoko, Tengo’s girlfriend, who tells him that Kyoko will no longer be able to visit (is she OK?). Ushikawa calls later, leading Tengo to believe that he might have had something to do with Yasuada’s call. Ushikawa demands an answer (well, a “yes” answer) on the grant. Tengo asks him point blank about the Little People and who Ushikawa is working for, but Ushikawa says that he is not at liberty to divulge that information. He says that Fuka-Eri and Tengo make a powerful team, each making up for what the other one lacks. Together they are carrying out what George Orwell had called a “thought-crime” (nice 1984 reference). Ushikawa says that he will give Tengo a little more time to change his mind.

Tengo continues to worry about Fuka-Eri and Kyoko, and end up going to visit his father, for only the second time, at the sanatorium where he is now living. On the train he reads a story about a man lost in a world of cats (!), a place where the man is meant to be lost. The phrase “place where he is meant to be lost” bothers Tengo.

While Tengo’s father has aged considerably, he is still physically healthy, although his mind wanders. He tells Tengo he is nothing, and Tengo suspects that his father is not actually his real father. He decides to read to him the story about the town of cats; his father tells him that they are filling some sort of vacuum, in the way that Tengo will himself fill the vacuum that his father leaves behind.

Tengo returns home from visiting the man he calls “Father”, the man who raised him as a son, but who might not actually be his father after all. After a good night’s sleep, though, he feels better — like he is an entirely new person. Two weeks pass uneventfully, but then, Fuka-Eri calls Tengo and asks if she can come visit. He tells her that strange things have been happening in conjunction with “Air Chrysalis,” and that the apartment might not be a safe place, but she comes anyway, with plans to stay for awhile. She tells him that the police have searched the Sakigake compound look for her, and found nothing about her parents – all of this is news to Tengo who has stopped reading newspapers. Fuka-Eri tells him that they need to join forces – a la Sonny and Cher.

Once again, Ushikawa visits Tengo at work and lays out his final deal: If Tengo accepts, he will be paid, and no harm will come to him in exchange for his silence. Tengo questions Ushikawa about Kyoko, but he denies any involvement. Ushikawa also “mentions” that they have information on Tengo’s mother, and that it is not pleasant. Tengo rejects the offer, and demands never to see Ushikawa’s ugly face again.

Tengo calls Fuka-Eri who tells him to hurry home, for something extraordinary is going to take place.

Some favorite parts and thoughts:

“I want you to tell me the truth,” the dowager said. ‘Are you afraid to die?’; Aomame needed no time to answer. Shaking her head, she said, ‘Not particularly – living as myself scares me more.”

When asked by the Dowager about not taking the initiative in seeing Tengo, “The most important thing to me is the fact that I want him with my whole heart.”

Tamaru born on Sakhalin Island – Chekhov’s book in Tengo’s narrative.

Chekhov and his line, “once a gun appears in a story, it has to be fired.’ “But this is not a story. We’re talking about the real world.” Tamaru narrowed his eyes and looked hard at Aomame. Then, slowly opening his mouth, he said, ‘Who knows?”

If you want to hear the Louis Armstrong recording of “Atlanta Blues,” with the clarinet solo by Barney Bigard that Tengo’s “girlfriend” (FWB is closer to the mark) loved so much, click here.

The sheer ugliness of Ushikawa.

“On first impression, Ushikawa honestly made Tengo think of some creepy thing that had crawled out of a whole in the earth – a slimy thing of uncertain shape that in fact was not supposed to come out into the light. He might conceivably be one of the things that Professor Ebisumo had lured out from under a rock.”

“Ushikawa narrowed his eyes and started scratching one of his big earlobes. The ears themselves were small, but Ushikawa’s earlobes were strangely big. Ushikawa’s physical oddities were an unending source of fascination.”

Tengo and Okawa’s Sinfonietta, Aomame and Szell’s.

Aomame and the gun: “She tested the weight of it in her hand. It was much lighter than it appeared to be. Such a small, light object could deliver death to a human being.” As opposed to her murder weapon of choice?

“A person’s last moments are an important thing. You can’t choose how you’re born, but you can choose how you die.”

“Chekhov was a great writer, but not all novels have to follow his rules. Not all guns in stories have to be fired.” Meta much?

“Not all guns have to be fired, she told herself…A pistol is just a tool, and where I’m living is not a storybook world. It’s the real world, full of gaps and inconsistencies and anticlimaxes.”

“I’m not afraid to die…What I’m afraid of is having reality get the better of me, of having reality leave me behind.”

I loved the whole section of Chapter 4, Tengo’s recollections of Aomame – it probably is the emotional core/center of the book.

“He depicted a world in which two moons hung side by side in the evening eastern sky, the people living in that world, and the time flowing through it. ‘Wherever this gospel is preached in the whole world, what this woman has done will also be told as a memorial to her.’”

Ayumi’s death – too much?

“Ayumi had a great emptiness inside her, like a desert at the edge of the earth. You could try watering it all you wanted, but everything would be sucked down to the bottom of the world, leaving no trace of moisture. No life could take root there. Not even birds could fly over it.”

The story of the vegetarian cat and the rat – what WAS the point?

Very long arms…in both Tengo and Aomame’s narratives.

“But who could possibly save all the people of the world?’ Tengo thought. ‘You could bring all the gods of the world into one place, and they still couldn’t abolish nuclear weapons or eradicate terrorism. They couldn’t end the drought in Africa or bring John Lennon back to life. Far from it – the gods would just break into factions and start fighting among themselves, the world would probably become even more chaotic than it is now. Considering the sense of powerlessness that such a state of affairs would bring about, to have people floating in a pool of mysterious questions marks seems like a minor sin.’”

“My wife is irretrievably lost. She can no longer visit your home in any form.” What do you think happened to Kyoko Yasuda?

“Tengo was not, strictly speaking, in love with Kyoko Yasuda. He had never felt that he wanted to spend his life with her or that saying good-bye to her could be painful. She had never made him feel that deep trembling of the heart. But he had grown accustomed to having this older girlfriend as part of his life, and naturally, he had grown fond of her. He looked forward to welcoming her to his apartment once a week and joining his naked flesh with hers.”

Ushikawa: “Once you pass a certain age, life becomes nothing more than a process of continual loss. Things that are important to your life begin to slip out of your grasp, one after another, like a comb losing teeth. And the only things that come to take their place are worthless imitations. Your physical strength, your hopes, your dreams, your ideals, your convictions, all meaning, or, then, again, the people you love: one by one, they fade away. Some announce their departure before they leave, while others just disappear all of a sudden without warning one day. And once you lose them you can never get them back.” Cheerful yes? But probably true.

“You people might have opened Pandora’s Box and let loose all kinds of things in the world….The two of you may have joined forces by accident, but you turned out to be a far more powerful team than you ever imagined. Each of you was able to make up for what the other lacked.”

Aomame returning to her childhood prayer to calm herself in the hotel.

Tengo’s story of the cat village – what does it mean? “It is the place where he is meant to be lost.”

Tengo’s “father” (is he?) telling him he’s nothing. “I am nothing,” Tengo said. “You are right. I’m like someone who’s been thrown into the ocean at night, floating all alone. I reach out, but no one is there, I call out, but no one answers. I have no connection to anything…”

“I have been filling in the vacuum that somebody else made, so you will in the vacuum that I have made. Like taking turns.”

What did you think of the scene between the Leader and Aomame?

Who or what is eating away at the Leader’s flesh?

“I’ve finally made it to the starting line.”

“Sonny and Cher,” Tengo said. “The strongest male/female duo.”

From Jay Rubin:

“As so often happens in a Murakami book, music provides a key to the workings of the novel. It is there in the opening sentences: ‘The taxi’s radio was tuned to a classical FM broadcast. Janacek’s Sinfonietta – probably not the ideal music to hear in a taxi caught in traffic.’ Aomame instantly recognizes the piece and even thinks about the conditions in Bohemia when it was composed in 1926. Not a classical music fan, she wonders how she could have known so much about – and felt so deeply and personally affected by – a composition she cannot remember having heard before. ‘[T]he moment she heard the opening bars, all her knowledge of the piece came to her by reflex, like a flock of birds swooping through an open window. The music gave her an odd, wrenching kind of feeling…a sensation that all the elements of her body were being physically wrung out.’

The source of this flood of musical knowledge is never revealed. In fact, the mystery only depends as we learn that it was not Aomame but Tengo who had a strong connection with Janacek’s Sinfonietta. He played the tympani part in his second year of high school, but that occurred long after Aomame disappeared from his life in the fifth grade, so she would not have known about that, either. From the time she hears it in the cab, however, Aomame thinks, ‘It makes me feel connected. It’s as if that music is leading me to something. To what, though, I can’t say.’

Obviously, the connections she feels is with Tengo, and the music is slowly leading her closer to him – very slowly, for these thoughts of hers occur in the second chapter of Book Three, 613 pages and six months after the opening scene, by which time, although she has still not met him…[PLOT GIVEAWAY HERE THAT I’LL SKIP}…it would be no problem at all for her ‘knowledge’ of Janacek’s Sinfonietta to come to Aomame directly from Tengo’s memory in that instant in the cab. In fact, it is precisely from that ‘wrenching’ moment, ‘the moment I heard Janacek’s Sinfonietta and climbed down the escape stairs from the traffic stairs from the traffic jam on the Metropolitan Expressway,’ that she has switched tracks from 1984 to 1Q84. ‘A strange world where anything can happen’ – even the construction of a joint U.S./U.S.S.R moon base. In 1Q84, a man can [another skip]…his early musical memories can suddenly leap into the mind of the woman he continues to love though he has not seen her for 20 years…

Murakami dramatized the near-impossibility of chance reunions in one of his earliest and most memorable stories, ‘On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl One Beautiful April Morning’ (1981). Occupying barely five pages in the translated collection The Elephant Vanishes, the story tells us how a perfectly-matched boy and girl, aged 18 and 16, tempt fate by separating in youth, convinced that they will find each other again if they are truly meant to be together. Tengo and Aomame, the boy and girl of 1Q84, are even younger, only ten years old, and they have barely even spoken to each other when events separate them, but both become convinced, as the result of that one electric moment of hand-holding in a fourth-grade classroom, that they were each other’s true loves, and both realize, at age 30, that the loneliness and emptiness of their subsequent lives are due entirely to each other’s absence. At first, they don’t want to do anything as practical as to actually look for each other. ‘What I want is for the two of us to meet somewhere by chance one day, like, passing on the street, or getting on the same bus,’ Aomame tells a friend.

In the short story, the young couple’s similar romantic notion is thwarted by a flu epidemic that nearly kills them and all but erases their memories of each other; when chance brings them together one April morning (yet another source for the April opening of 1Q84), they feel only the faintest glimmer of recognition before they part forever.’ The novel replaces the simple flu epidemic with a wildly elaborated series of events that turn the girl into a sexually adventurous vigilante killer and the boy into a passive lover and unfulfilled novelist involved in a literary fraud, but their memories from elementary school remain stunning clear, and they grow determined to find each other.

The emotional core of the novel is to be found in Book Two, Chapter 4, when childhood memories begin flooding back to Tengo in a supermarket. Picking up a sprig of edamame (green soybeans on the branch), he is instantly reminded of Aomame (‘green peas’) and realizes how much she meant to him. We have seen this kind of love before in Murakami’s fiction, an attachment rooted in childhood, and not just in ‘On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl One Beautiful April Morning.’ In South of the Border, West of the Sun, Hajime and Shimamoto drew close at the age of twelve and had one memorable moment of holding hands. Their adult affair is a return to those innocent times. In Norwegian Wood, Toru and Midori pledge their love amid the children’s rides in a rooftop play area…That fourth-grade classroom was an emotional crucible for them, as hinted at when Aomame first enters the world of 1Q84, passing through a construction materials storage area that is ‘about the size of an elementary school classroom.’ (MY NOTE: Now that I didn’t notice.) The stories of Aomame and Tengo’s loveless childhoods are the most affecting parts of the novel, and Tengo’s memories go even deeper, all the way to infancy.

Murakami himself has said that the tiny ‘On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl One Beautiful April Morning’ was the seed from which the three-volume grew, but by planting that seed in 1Q84, he made it possible for the lovers to be reunited instead of parting forever. Leader tells Aomame she would never have even thought of searching for Tengo in the ordinary world of 1984. There is only one Big Brother who controls the ultimately romantic world of 1Q84, and his name is Haruki Murakami.”

Your thoughts? Questions?

My next post: Tuesday, October 2, Book 2, Chapters 11-18

Enjoy.