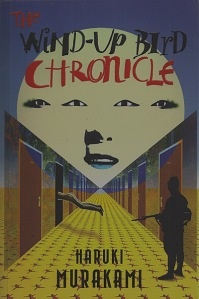

The Wind-up Bird Chronicle

Chapters 1-8

By Dennis Abrams

Instead of a straight forward synopsis (unless you all really want one) I’m going to open with a few observations and favorite bits and impressions:

I love how on just the first page we’ve got spaghetti, Rossini, and the beginning of the “mystery.”

It took him an entire 15 pages to get to his first description of an ear: “…her hair swung away to reveal a beautifully shaped ear, smooth as if freshly made, its edge aglow with a downy fringe.”

Another husband who does the cooking.

A missing cat.

“Is it possible, finally, for one human being to achieve perfect understanding of another? We can invest enormous time and energy in serious efforts to know another person, but in the end, how close are we able to come to that person’s essence? We convince ourselves that we know the other person well, but do we really know anything important about anyone?” I have a feeling this is what the book will be, at least in part, about.

The humor (and sadness) of Toru and Kumiko’s argument about blue tissues and flower-pattern toilet paper and her disappointment that he didn’t know she hated them. And green peppers. “You’ve been living with me all this time,” she said. “but you’ve hardly paid any attention to me. The only one you ever think about is yourself.”

The well in the Miyawaki’s yard, Kumiko telling Toru “Maybe you’ve got this deep well inside, and you shout into it, ‘The king’s got donkey ears!’ and then everything’s OK.”

More sandwiches

Toru’s lack of distinguishing characteristics.

The missing polka-dot tie. The thin layer of dust on his brown shoes.

The mysterious Malta Kano. Her red vinyl hat.

“There was something strange about her eyes. They were mysteriously lacking in depth. They were lovely eyes, but they did not seem to be looking at anything. They were all surface, like glass eyes. But of course they were not glass eyes. They moved, and their eyes blinked.”

Malta and water.

Malta’s younger sister, raped by Toru’s brother-in-law, Noboru Wataya.

Why did the cat leave? “That I cannot tell you. Perhaps the flow has changed. Perhaps something has obstructed the flow.”

“Mr. Okada,” she said, “I believe that you are entering a phase of your life in which many different things will occur. The disappearance of your cat is only the beginning.”

“Different things,” I said. “Good things or bad things?”

She tilted her head in thought. “Good things and bad things. Bad things that seem good at first, and good things that seem bad at first.”

Kumiko’s good day. The importance of the cat.

Mr. Honda. First talk of World War II, Manchuria/Mongolia.

Again, flow. “The point is, not to resist the flow. You go up when you’re supposed to go up and down when you’re supposed to go down. When you’re supposed to go up find the highest tower and climb to the top. When you’re supposed to go down, find the deepest well and go down to the bottom. When there’s no flow, stay still. If you resist the flow, everything dries up. if everything dries up, the world is darkness.” ‘I am he and/He is me: Spring nightfall.’ Abandon the self, and there you are.’”

“Just be careful of water.” I have a feeling this is an important warning. Given wells and flow and all.

Finding the tie at the cleaners – easy listening music.

The wind-up bird winding its spring.

The stone bird, whistling “Thieving Magpie.”

“Somebody told me gays are lousy whistlers. Is that true?”

Toru Okada introduces himself to May Kasahara. Does May remind anyone of the chubby girl in Hard-boiled World?

The dried up well. “I leaned over the edge again and looked down into the darkness, anticipating nothing in particular. So, I thought, in a place like this, in the middle of the day like this, there existed a darkness as deep as this.”

Kumiko and Noboru’s stories. “Noboru Wataya was young and single and smart enough to write a book that nobody could understand.”

Toru’s intense dislike of his brother-in-law. “He was a despicable human being, an egoist with nothing inside him. But he was a far more capable individual than I was.”

Another sandwich.

Creta Kano. “She did a remarkable job of preserving the look of the early sixties. She wore her hair in the bouffant style I had seen in the photograph, the ends curled upward. The hair at the forehead was pulled straight back and held in place by a large, glittering barrette. Her eyebrows were sharply outlined in pencil, mascara added mysterious shadows to her eyes, and her lipstick was a perfect re-creation of the kind of color popular back then. She looked ready to belt out ‘Johnny Angel’ if you put a mike in her hand.”

Creta’s story. An Inquiry into the Nature of Pain.

The dryness of this:

“Just as Malta had to find her own way by herself, I had to find my own way by myself. And when I turned twenty, I decided to kill myself.”

Creta Kano took up her cup and drank her remaining coffee

“What delicious coffee!” she said.

Love it.

A life without pain becomes a life without feeling

From Matthew Strecher’s Haruki Murakami’s The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, an interesting perspective on the book:

“A Walk Around the Brain”

“Another review, somewhat less concerned with the chaotic nature of the story, comes from David Mathew, whose more upbeat commentary “On the Wind-up Bird Chronicle from a Rising Son’ came out on-line some months after the novel was released in the United Kingdom in 1999.

Calling The Wind-up Bird Chronicle ‘an incredible achievement,’ Mathew hits very accurately on the central motivation of the story: ‘This is a novel which endeavours to explain what it is to be a young man with a flexible approach to his own life: will life break him or merely bend him? What happens when routine is abolished? What does it mean: to be alone?”

Mathew…notices the flaws in the novel, and these are unavoidable. The text is, as he notes, ‘frequently meandering, occasionally baffling, repetitive or overwritten…’ This, too, is a regular aspect of Murakami’s writing, and it can be exasperating. But Mathew also reflects on the fact that Murakami’s style is the result of the author’s distaste for planning his stories; instead, he allows them to flow directly from his imagination onto the page. ‘[T]he author is well known to prefer freefalling through his novels, rather than planning, and a certain cumulative force is felt during the reading, possibly as a result of this technique (or lack of technique); writes Mathew. On this subject Murakami himself frequently tells interviewers that he himself does not know where his stories will go. Speaking to Salon in 1997, the author says of The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, ‘I was enjoying myself writing, because I don’t know what’s going to happen when I take a ride around that corner…it’s very exciting when you don’t know what’s going to happen next. The same thing happens to me when I’m writing. It’s fun.’

Ultimately, Mathew finds something fresh and exciting in the fact that The Wind-up Bird Chronicle is, by and large, a walk around the lead character’s brain,’ despite the fact that ‘some of it is disorganized, some of it is unwanted ephemera.’ But, after all, the inner mind is not a well-organized machine, but a place of dark, disturbing forces, containing the roots of identity, but also the potential for madness. How can one really discuss chaos in concrete, logical terms, much less expect a well-reasoned conclusion?”

From Jay Rubin, quoting from a lecture Murakami gave at Princeton in 1992, which gives an idea of what constitutes “pure” Japanese literature,” and where his works stand in opposition:

“It seems to me that in a country like America, with its ethnic variety, communication is a matter of special importance. Where you have whites and blacks and Asians and Jews and people of all different cultural and religious backgrounds living together, what is needed to convey one’s ideas clearly is not in-group complacency but writing styles that have an effect ton a broad range of people. This calls for a broad range of rhetorical devices and storytelling and humor.

In Japan, with its relatively homogeneous population, different literary customs have evolved. The language used in literary works tends to be the kind that communicates to a small group of like-minded people. Once a piece of writing is given the seal of approval with the label junbunaku – ‘pure literature’ – the assumption takes hold that it only needs to communicate to a few critics and a small segment of the populace there’s nothing wrong with writing like that, of course, but there’s nothing that says that all novels have to be written this way. Such an attitude can only lead to suffocation. But fiction is a living thing. It needs fresh air.

The fact remains, of course, that whatever I may have found in foreign literature, I wanted to write – and I continue to write – Japanese fiction. Using new methods and a new style, I am writing new Japanese stories – new monogatari. I have been criticized for not using traditional styles and methods, but, after all, an author has the right to choose any methods that feel right to him.

I have been living in America for almost two years now, and I feel very much at home here. If anything, I am more comfortable here than in Japan. I am still very much aware, however, that I was born and raised in Japan, and that I am writing novels in Japanese. Furthermore, my novels are always set in Japan, not in foreign countries. This is because I want to portray Japanese society using the style that I have created. The longer I live abroad, the stronger this desire of mine becomes. There is a tradition whereby Japanese writers and artists who have lived abroad come home with new feelings of nationalism. They undergo a re-conversion to Japan and sing the praises of Japanese food and Japanese customs. My case is rather different. I like Japanese food and Japanese customs, of course, but what I want to do is live in a foreign country, observe Japan from here, and write what I see in novels.

I am now writing a new novel, and as I write I am aware that I am changing bit by bit. My strongest awareness that I have changed is this new awareness that I must change. Both as a writer and as a human being. I have to become more open to the world around me. I know. And I know, too, that in some cases I am going to have to engage in a struggle.

For example, until I came to America, I had never spoken like this before an audience. I had always assumed that there was no need for me to do such a thing because my job is to write, not to speak. Since coming to live in America, however, I have gradually begun to feel that I wanted to speak to people. I have come to feel more strongly that I want the people of America – the people of the world – to know what I, as one Japanese writer, am thinking. This is an enormous change for me.

I feel certain that novels from now on will have a far more diverse mixture of cultural elements. We see this tendency in the writings of Kazuo Ishiguro, Oscar Hijuelos, Amy Tan, and Manuel Puig, all of whom have taken their works beyond the confines of a single culture. Ishiguro’s novels are written in English, but I and other Japanese readers can feel in them something intensely Japanese. I believe that in the global village, novels will become in this way increasingly interchangeable. At the same time, I want to go on thinking about how, in the midst of such a powerful tide, people can manage to preserve their identities. What I must do, as one novelist, is to carry this thought process forward through my work of telling stories.”

Rubin continues:

“The ‘new novel’ of which Murakami speaks is, of course, The Wind-up Bird Chronicle which had just begun to be serialized in the Japanese magazine Shincho. This massive project would occupy most of his time and energy for the next three years. Having grown out of the story ‘The Wind-up Bird and Tuesday’s Women,’ Books One and Two of the novel were published simultaneously on Tuesday, 12 April 1994; the 500-page Book Three, however, finally appeared on Friday, 25 August 1995. Murakami was exhausted, as he had been after writing Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World.

South of the Border, West of the Sun and The Wind-up Bird Chronicle may have appeared separated from each other ‘through a mysterious process of cell division,’ but the points of contact lie in the shared theme of the difficulty of one person’s knowing another and the affluent 1980’s setting. Where South of the Border, West of the Sun might be seen as a novel-length exploration of the mystery of ‘The Elephant Vanishes,’ The Wind-up Bird Chronicle opens up new areas of exploration. It is a sprawling work that begins as a domestic drama surrounding the disappearance of a couple’s cat, then transports us to the Mongolian desert, and ends by taking on political and supernatural evil on a grand scale. Longer than Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, it was clearly a turning point for Murakami, perhaps the greatest of his career. As Murakami said, this is where he finally abandons his sense of cool detachment to embrace commitment, and though much of the action still takes place in the mind of a first-person Boku narrator, the central focus of the book is on human relationships.

This was a bold move for a writer who had built his reputation on coolness, but Murakami had come to feel strongly that ‘mere’ storytelling was not enough. He wanted to care deeply about something and to have his hero’s quest lead to something.”

Thoughts so far? Questions?

My next posts: Friday, June 20th on translation and more, then Tuesday, June 24th, on The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, Chapters 9-13, Chapters 1-2. How’s the pace for everyone? Too fast? Too slow? Let me know in the comments!

And enjoy.