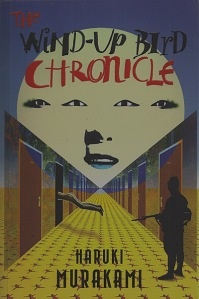

The Wind-up Bird Chronicle

Conclusion

by Dennis Abrams

——————-

To continue with Strecher:

“[Mamiya’s] ordeal, however, is not over. In a much later narrative, passed on to Toru in a long letter, Mamiya relates how he managed to survive the massed attack of a Soviet armored division in the final days of the war, and found himself, minus one hand, alive in a Soviet labor camp after the war. There, again, he meets Boris the Manskinner, who starts out as a fellow inmate but will shortly take over control of the camp. In time Mamiya gains Boris’ confidence, hoping for a chance to take revenge on him. Unfortunately for Mamiya, however, he cannot kill Boris. Even given two easy opportunities to blow his enemy’s head off at pointblank range, he is unable to do so. Eventually he returns to Japan, bearing Boris’ final curse on him: ‘Wherever you may be, you can never be happy. You will never love anyone or be loved by anyone. That is my curse. I will not kill you. But I do not spare you out of goodwill. I have killed many people over the years, and I will go on to kill many more. But I never kill anyone whom there is no need to kill.’ And true to this prophesy, Mamiya lives out the rest of his days in quiet misery, an ‘empty shell’ of a man.

The purpose of Mamiya’s narrative, I think, is to provide a historical pattern, a narrative ancestor, to the situation in which Toru finds himself in the present. The relationships established here are of critical importance: Mamiya, a force of good, opposes Boris, the embodiment of evil. Two worlds collide, one of controlled gentility and forbearance – something also displayed by Toru…the other of pure malevolence and ambition. In that struggle between elementary forces, Mamiya loses everything; his failure to destroy this evil presence costs him his soul. Cast into archetypal terms, as I believe we must with the whole of The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, Mamiya fails to restore life to the wasteland of death (seen both in the wilds of the Mongolian desert and the labor camp in barren Siberia) that remained following World War II.

But there is another, equally important, subnarrative to the saga of Mamiya in the war, and this is the tension that is established between the will of the individual and the power of the State. Murakami himself is primarily interested in this aspect of the war as part of his project of recovering the individual voices of those who were involved. Indeed, the same impulse that led the author to seek the fuller story of the sarin gas incident, including the first-hand views of the cult members themselves, leads him to wonder what role government plays – especially a strict, militaristic one such as ruled Japan at that time – in the atrocities committed during war. ‘It is the same with the Rape of Nanking,’ Murakami commented in 1997. ‘Who did it? The military or the individual soldiers? Just how responsible are individuals to a society where they relinquish their free will to the system?’

Murakami does not absolve those who commit atrocities, but he does suggest the possibility of mitigating circumstances, particularly the lack of individual freedom at times of international tension. Sometimes individual evil and ambition cause suffering, as we see in the case of Boris the Manskinner, but even Boris represents not so much an individual but a system, of which he is a part. Without the Soviet system, there might be no Boris. Similarly, were there no Japanese State, there might be no war, and thus no need to carry out stupid orders that waste human life.

We see signs of dissent and hostility toward the Japanese State, whose leaders’ arrogance and ambition led to disaster, in the comments of many of those involved. Hamano expresses it to Mamiya – an act in itself that could have been regarded as treason – as they sit on the wrong side of the Khalkha River in Soviet-held territory: ‘I’m telling you, Lieutenant, this is one war that doesn’t have any Righteous Cause. It’s just two sides killing each other. And the ones who get stepped on are the poor farmers, the ones without politics or ideology…I can’t believe that killing these people for no reason at all is going to do Japan one bit of good.’

This is the common soldier’s perspective, one echoed later by the lieutenant put in charge of executing Chinese prisoners. But the overview, the hostility toward the politics of the war, is best and most succinctly expressed by Honda as he shows his bitterness of the aftermath of the Nomonhan disaster of 1939.

‘Nomonhan was a great embarrassment for the Imperial Army, so they sent the survivors where they were most likely to be killed. The commanding officers who made such a mess of Nomonhan went on to have distinguished careers in central command. Some of the bastards even became politicians after the war. But the guys who fought their hearts out for them were almost all snuffed out.’

Although we are unaware of it so early in the novel, this is the first step toward establishing a link between the events of 1939-1945 (Nomonhan through the end of the war) and the events surrounding Toru and Kumiko now, for the springboard used by Noboru Wataya to enter politics is his uncle, Yoshitaka Wataya, a member of the Diet who was at one time connected with the very members of central command who had begun the disastrous war against China. Noboru, following in these footsteps, demonstrates that the dark side of the State persists, exerting its ugly influence over the ordinary people.

Murakami’s fiction has, of course, posed this sinister aspect of the Japanese State for many years – indeed, it is a central element in A Wild Sheep Chase, and becomes even more pronounced in Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. World War II, however, is the ideal vehicle for the pursuit of this theme, for it is war, as he put it to interviewer Ian Burama in 1996, that ‘stretches the tension between individuals and the state to the very limit.’

The third major narrative of this novel emerges entirely in Book Three (‘The Birdcatcher’), and concerns the enigmatic characters Nutmeg Akasaka and her son, Cinnamon. More closely tied to the original narrative of Toru and his quest for Kumiko, this final story provides the necessary path by which the mystery of Kumiko’s disappearance, the real nature of Noboru’s plot, may be approached. It also offers a plausible, if puzzling, explanation of what the ‘wind-up bird’ of the title is really supposed to be. Indeed, we might look upon Book Three as Murakami’s attempt to reconnect the disparate events in Books One and Two.

Nutmeg Akasaka makes her first appearance in Book Two, but we have no more idea than Toru about who she is, or how much she will figure into the story later. Toru sits outside Shinjuku Station, watching the people go by, following his uncle’s advice to sit and clear his head for awhile, when a woman, well dressed and attractive, approaches him and stares at the mark on his face. She asks him if he needs anything, but when he replies in the negative, she leaves.

The woman returns in Book Three, and this time there is something Toru needs from her: he needs money, for he has decided to purchase the land on which the well he needs so much is located. The sum required, eighty-million yen (more than half a million U.S. Dollars), is a considerable one, and it is to the evidently wealthy Nutmeg that he turns for help.

In response, she employs him in a most peculiar position for which he is uniquely qualified: Toru becomes a ‘healer’ of sorts, a medium by which women who suffer from a mysterious unconscious imbalance restore their internal equilibrium. The process by which they are healed is, for Toru, both passive and sexual; as he sits blindfolded in a darkened room, his mind blank, the women kiss, fondle, and caress the mark on his cheek.

But the structure of the third narrative is more complex than this, for it encompasses both the physical and metaphysical aspects of the central narrative (Toru and Kumiko) in its focus on sexuality and the unconscious, and at the same time brings to bear the historical significance of the World War II, the power of the State, and the risks of playing with the inner consciousness.

Most of this third narrative is revealed to us through Nutmeg’s mute son, Cinnamon, a refined youth of about twenty. Through certain asides, unattributed, we learn that Cinnamon lost his ability to speak through a strange incident that occurred when he was very young. Waking one night to investigate the cry of a bird he has never heard before, he spots two men, one of whom looks like his father, burying a small bag under a tree in the family’s garden. The man who looks like his father climbs the tree, never to return. After watching for a while he goes back to bed, but later dreams that he has gone out to the garden to dig up the bag, which turns out to contain a human heart, still beating.

When he returns to bed, he finds another ‘him’ sleeping in his bed. He panics, fearing that if there is another ‘him,’ then he himself will no longer have a place in the world. IN order to preserve his existence, he forces his way into the bed with the other ‘him’ and goes to sleep. When he wakes the next morning, he discovers that he no longer possesses a voice.

From this time on the boy – later known to us as Cinnamon – seems to live in two worlds; one that is shared by his mother and other family members; and another, inner world of his own. Later we come to suspect that that this ‘inner world’ is the same as the unconscious hotel in which Toru seeks Kumiko. For Cinnamon, this takes the form of cyberspace, the mysterious interior of his computer network, to which he gradually allows Toru (limited) access.

There is no question of what that inner space means to Cinnamon: it is the key, if he can only unlock it, to the meaning of his life, and the answer to why his voice was taken from him. To do this, Cinnamon creates stories (again, the power of the story is revealed!). This is a practice first begun with his mother, who used to play a game with him of making up stories about her own father, a veterinarian with the Imperial Army in Manchuria who bore a mark on his right cheek virtually identical to Toru’s. How much truth there is in the stories it is impossible to say, for Nutmeg’s father disappeared after the Soviet invasion in the last days of the war. But this is not the point; these stories, which are connected with those of Mamiya and Honda in their expression of tension between individual Japanese soldiers and the Japanese central command, are designed not to reinvent the life of the actual man who was Cinnamon’s grandfather, but to help Cinnamon to understand (and create) himself. Toru recognizes this after having been permitted a brief glimpse of one of the stories in Cinnamon’s computer:

‘I had no way of telling how much of the story was true. Was every bit of it Cinnamon’s creation, or were parts of it based on actual events?

I would probably have to read all sixteen stories to find the answers to my questions, but even after a single reading of #8, I had some idea, however vague, of what Cinnamon was looking for in his writing. He was engaged in a serious search for the meaning of his own existence. And he was hoping to find it by looking into the events that had preceded his own birth.’

The stories, no doubt at least nominally grounded in those his mother had told him about his grandfather, are filled with the violence and misery of the final weeks in Manchuria, during which the Imperial Army, hopelessly outnumbered, prepared to make its last stand against the Soviet armored units assembling for their final assault on them. The first story concerns the killing of animals at the Hsin-Ching zoo in order to prevent them from being accidentally released once the Soviets have invaded. This task is assigned to an intelligent young lieutenant who has no stomach for the job, and in the end leaves it only partially completed.

We gain a better sense of the lieutenant’s attitude toward the war and his role in it in a later story in which he is given the job of executing eight Chinese prisoners, members of the local military academy’s baseball team who have attempted to flee the city in its final days. The lieutenant’s impressions, conveyed to the veterinarian (Nutmeg’s father) are similar to those of ‘Hamano’ in Mamiya’s earlier narrative.

‘Just between you and me, I think the order stinks. What the hell good is it going to do to kill these guys? We don’t have any planes left, we don’t have any warships, our best troops are dead. Some kind of special new bomb wiped out the whole city of Hiroshima in a split second…We’ve already killed a lot of Chinese, and adding a few bodies to the count isn’t going to make any difference. But orders are orders.’

In this brief statement, the lieutenant expresses the ‘tension between individuals and the state’ that interests Murakami so much. What is one to go when given orders that make no sense, that merely reassert the stupid brutality of those in charge? Much of the brutality of the war, he suggests, is attributable not to individuals but to the State that commands them.

Another important aspect of Cinnamon’s subnarrative on the computer is its recreation of the ‘wind-up bird’ itself, linking the narrative to earlier phases of the novel. The wind-up bird in Cinnamon’s narrative world is a spectral creature, audible only to certain gifted (or cursed) people, and visible to none. Its eerie cry emerges at moments of great tension, such as when the animals at the zoo are shot, or when the Chinese prisoners are executed. Its cry also coincides, roughly, at least, with tiny, parenthetical prophesies about individual characters in the story. We are told, for instance, the final fate of the soldier under the lieutenant’s command who can hear the bird’s cry.

Finally, we are given the impressions of Cinnamon’s grandfather, and these are significant mainly because they tell us more about Cinnamon himself. Observing the executions of the Chinese prisoners, for instance, the veterinarian imagines himself to be split into two distinct halves, both executioner and executed. ‘The veterinarian watched in numbed silence, overtaken by the sense that he was beginning to split in two. He became simultaneously the stabber and the stabbed. He could feel both the impact of the bayonet as it entered his victim’s body and the pain of having his internal organs slashed to bits.’ This dualism is equally an aspect of Cinnamon, who was ‘split in two’ at the age of six. It is also a link with others in the novel who have experienced the same thing: Creta Kano, Kumiko, Nutmeg, and indeed Toru himself. At the same time, it provides a physical visceral quality to that sensation, linking it to the skinning of Yamamoto, and eventually to the murder of Nutmeg’s husband, whose body is found with all its internal organs missing.

The third narrative, then, manages to bring together many of the disparate elements of the first two: the clashing historical periods, the dichotomy between physical and metaphysical, the gap between the conscious and unconscious worlds. It even gives a common metaphorical reading, in the form of the computer, to the mystery of the unconscious. Cinnamon’s narrative manages to close the gaps between the three narratives, tying together elements that appeared unrelated at the end of the first two books.

By this time it must be reasonably clear that what really connects the three disparate narratives that make up The Wind-up Bird Chronicle is a crisis of identity that is both physical and metaphysical, real and magical. It is born of the separation, so to speak, of the various elements that make up one’s identity: a ‘core’ identity that resides within one, and the sum of one’s experiences and interactions with others. Identity is, naturally, tided to the individual will, but in this novel that will is constantly threatened by the controlling power of the State and its organs. In that sense the work can be read as a quasi-political novel, one of resistance to the State. On a more basic level, however, the novel depicts a more archetypal conflict between good and evil, the resolution of which has the potential to return fertility to the wasteland.”

…….

“Creta Kano’s experience [with Noboru Wataya] at once a physical and a metaphysical one, helps us to understand a little better some of the other physical mutilations in the story. We might comprehend, for instance, the murder of Nutmeg’s husband, whose body is found with all its internal organs removed and the face slashed to bits, as a similar, brutally physical attempt to remove both his external identity (his face) and his internal ‘core’ (his organs). Murakami’s focus on the organs in the abdominal cavity does have some cultural significance here that is worth noting. Unlike in the West, where the soul is thought to exist in the mind, or sometimes in the heart, Japanese tradition has it that the center of one’s being exists in the belly. This, according to some, is the origin of seppuku, ‘belly cutting,’ known in the West as ‘hara-kiri.’ Opening the abdomen by disembowelment literally opens the true essence of the individual, and thus is taken as a last demonstration of truth. This may helps us to understand the executions of the Chinese baseball players in Cinnamon’s story: looking beyond the practical reasons for bayoneting the prisoners (to save ammunition), the mutilation of their internal organs tear to pieces their ‘core selves’ as well as their bodies. It may also help explain why, despite having been beaten to death with a baseball bat, the last victim of this massacre still manages to sit up and grab the veterinarian by the hand. His ‘core’ has not yet been fully extinguished, and that ‘something’ within him still struggles to exert its own existence.

We gain a very clear picture of the physical side of the core identity quite early in the story from May Kasahara as well. She describes it as the ‘lump of death,’ but in the context of the above discussion we can understand that she really refers to the ‘core identity’ itself.

‘…the lump of death. I’m sure there must be something like that. Something round and squishy, like a softball, with a hard little core of dead nerves…it’s squishy on the outside, and the deeper you go inside, the harder it gets…and the closer you get to the center, the harder the squishy stuff gets, until you reach this tiny core. It’s sooo tiny, like a tiny ball bearing, and really hard.’

It is this ‘something (nani ka, an expression that recurs throughout the novel) that obsesses everyone in the story. Mamiya, despite his obviously unpleasant associations with wells, still feels the urge to climb down into any well he sees. Why? ‘I probably continue to hope that I will encounter something down there,’ he tells Toru, ‘that if I go down inside and simply wait, it will be possible for me to encounter a certain something…What I hope to find is the meaning of the life I have lost. By what was it taken away from me, and why?’ these are almost the same words used by Creta Kano in describing her experience with Noboru Wataya.

In sum, then, The Wind-up Bird Chronicle is about the ‘core’ identity of the individual, how it can be located, understood, protected, or alternatively, removed or destroyed. It also lies at the heart of Kumiko’s disappearance for, as we later discover, Kumiko’s inner core has also been tampered with, leaving her lost, uncertain of who, or where, she really is.

We now approach one of the really difficult aspects of this novel: the question of how the core identity is corrupted. The process is, I believe, one of division. That is, the entire Self (conscious ‘self’ and unconscious ‘other’) is divided in two, and from between them, the ‘core’ is removed. Without this essential link to the central body of memory and information there can be no real connection between them, and thus no possibility of the necessary communication that creates a ‘whole’ person.

This is what has happened to Kumiko. Like Creta Kano, she has been stripped of her core identity, leaving her conscious and unconscious selves divided and lost. One exists somewhere in the conscious realm – we never learn where – while the other lives in the unconscious, the mysterious hotel, in ‘Room 208.’

We cannot help noticing the opposite nature of these two sides of the same person. The Kumiko know to Toru as his wife, for instance, seems to be a perfectly ordinary young woman, an intelligent professional, leading a reasonably normal married life with him. But her unconscious ‘other’ is a mirror image of this Kumiko, sexually charged and driven by pure physical desire. This ‘other’ that has always lurked within Kumiko has remained suppressed by the conscious Kumiko, but is nevertheless a critical part of her What Noboru has done in removing her core identity is to eliminate the central reference point by which the conscious Kumiko keeps the unconscious side of herself under control thus released, the ‘other’ Kumiko is free to express herself in a characteristically sexual way. In one sense this is healthy; Toru’s wife confesses that she never found sexual fulfillment with him, perhaps because she maintained such a tight control over her ‘darker side.’ At the same time, however, it leaves her conscious self in a weakened position of submission, helpless against the power of her inner sexual desire.

Toru, of course, takes on the role of saving Kumiko from his fate, but his task is complicated by the fact that he too must struggle against the power of his unconscious ‘other.’ Compounding the difficulty of this task is that this ‘other side’ of Toru is Noboru himself.

This leads to an interesting question: If the ‘other’ exists in the realm of the unconscious, how then does Toru encounter his own ‘other’ in the conscious world? The answer lies in the concept of the ‘nostalgic image,’ something I have discussed at length in several previous writings on Murakami.

The concept of the nostalgic image is fairly straightforward, but demands a leap of faith on the part of readers, because it is heavily dependent on the magical elements in the text. It refers to a recurring motif in Murakami fiction in which the protagonist longs desperately for someone or something he has lost – a friend, a lover, an object – and in response, his unconscious mind, using his memories of the object or person in question, creates a likeness, or a surrogate, which then appears in the conscious world as a character in the story. There is, however, one major catch: nothing ever really looks quite the same in both worlds. Thus, to the protagonist as well as the hapless reader of Murakami fiction, the relationship between the ‘nostalgic image’ character and its origin is often obscure. This much is hinted in the final lines of Hear the Wind Sing, in a quote ostensibly from Friedrich Nietzsche: ‘We can never comprehend the depths of the gloom of night in the light of day.’ In the context of Murakami’s fictional world this means that nothing passes from the unconscious into the conscious world without experiencing some kind of radical transformation in appearance.

Nevertheless, we can usually spot these ‘image characters’ by their peculiarity: nameless twins and a talking pinball machine in Murakami’s second novel, Pinball 1973; the ‘Sheepman, made up of the protagonist’s unconscious conceptions of Rat and the Sheep in A Wild Sheep Chase; the strange little people, some seven-tenths of normal size, who invade the home of a man in the short story ‘TV People;’ the opaque image of a middle-aged woman who appears on the protagonist’s back in ‘The Story of the Poor Aunt;’ and so on.

Forming the connection between the unconscious memory and the image it becomes is usually a matter of linguistic relationship. For instance, a dead girlfriend from the protagonist’s student days named Naoko reappears as a pinball machine known as ‘the Spaceship.’ The connection lies in the fact that Naoko used to tell him stories about people on other planets. In the same novel, the protagonist’s missing friend ‘Rat’ emerges as ‘the Twins,’ nameless girls who suddenly turn up on either side of him one morning after a night of heavy drinking. In attempting to find some suitable names for them (reminding us of Nutmeg and Cinnamon), the protagonists comes up with ‘Entrance’ and ‘Exit,’ which leads him to think about things without exists, such as mousetraps, and this finally leads to Rat.

Similar ‘ image characters’ appear in The Wind-up Bird Chronicle. It is possible to read the characters of Creta and Malta Kano, for instance, as images of Kumiko and her older sister, a character Toru knows only through Kumiko’s stories of her. The relationships and experiences are similar. Kumiko, for instance, suggests that she might have handled her difficult childhood better had her sister not died, thus denying her a confidant. Creta Kano, on the other hand, describes her own trials with pain, attempted suicide, and identity crisis in the absence of her sister, who was performing mystical divinations on the island of Malta during these critical years. We note also the various incarnations of Creta Kano – one living in pain, another in numbness, and finally one who balances the two – and perhaps think of the two ‘sides’ of Kumiko: one who is ‘numb’ to Toru’s sexual caresses, and another caught up in a torrent of uncontrollable sexual abandon.

Other clues, a little more prosaic, also suggest a correlation between Kumiko and Creta. The fact that Creta Kano is exactly the same size as Kumiko and is thus able to slip into her clothing with no difficulty is suggestive. We might also note the retro-look affected by Creta Kano that suggests her roots in a previous time; she is a mixture of Kumiko past and present. Finally, there is the slippage in identity between Creta and the ‘Telephone Woman’/Kumiko during their sexual encounter with Toru in the unconscious hotel room.

But more than anything it is the similarity of her experience with Kumiko’s – and the central role of Noboru Wataya – that is suspicious. The scene in which Noboru draws out Creta Kano’s core consciousness, for instance, has the unmistakable signs of childbirth, or of an abortive birth. Might the ‘defilement’ of Creta not be another way of looking at the operation in which Kumiko’s own fertility is negated? Finally, there is the dream in which Malta tells Toru that her sister has given birth to a baby, and named it Corsica; this, Toru tells May Kasahara at the end of the novel, is what he will call his baby if he and Kumiko should have one.

Another character who bears a strong image quality is ‘Ushikawa,’ an unsavory little man who acts as go-between for Toru and Noboru in the latter stages of the book. Readers of A Wild Sheep Chase will certainly recognize similarities between this man, whom Toru describes as ‘without question, one of the ugliest human beings I had ever encountered…less like an actual human being than like something from a long-forgotten nightmare,’ and the ‘Sheepman,’ whose unkempt appearance is the more unique for the fact that he walks around in an ill-fitting, poorly-stitched sheep suit.

But the point is less their grotesque appearance than their function. Just as the ‘Sheepman’ is a combination of Rat and the antagonist Sheep, ‘Ushikawa seems to be created out of Kumiko, on the one hand, and his arch-nemesis Noboru, on the other. The association with Kumiko helps us to understand both ‘Ushikawa’s’ evident closeness to her (‘I’m taking care of her,’ he tells Toru cryptically), and yet his lack of knowledge about the details of her imprisonment (‘Not even I know all the details.’) the connection to Noboru, (who, lest we forget, is also part of Toru) accounts for his violent side, expressed in how he used to beat his wife and children. We can also hear the warning, megalomaniacal tones of Noboru in ‘Ushikawa’s’ assertion that Noboru ‘has a very real kind of power that he can exercise in this world, a power that grows stronger every day.’ This is Noboru speaking directly to Toru.

…

“As Creta Kano says, Noboru is the opposite of himself, existing in a ‘different world.’ This opposition is manifested in their behavior throughout the novel; whereas Toru is a mild, passive, unobtrusive figure, Noboru is violent, dominant, and ambitious. Yet there is crossover, or rather, there are points when this dark, violent side overcomes him, just as Kumiko’s dark, sexual side gradually takes hold of her. We see Toru lose control of himself in the scene when he beats the guitar player with his own baseball bat.

‘My mind was telling me to stop. This was enough. Any more would be too much. The man could no longer get to his feet. But I couldn’t stop. There were two of me now, I realized I had split in two, but this me had lost the power to stop the other me.’

This enraged Toru is, one supposed, a manifestation of Noboru, who gains strength in the darkness and takes control of Toru’s actions in the real world. We might note in passing that Toru’s description above is almost identical to ‘Ushikawa’s monologue about beating his wife and children, hinting at the connection between them:

‘I’d try to stop myself, but I couldn’t. I couldn’t control myself. After a certain point I would tell myself that I had done enough damage, that I had to stop, but I didn’t know how to stop.’

The object of ‘Ushikawa’s’ beating vis-à-vis the object of Toru’s is not important here; what matters is the expression of uncontrollable violence, for as Toru listens to ‘Ushikawa,’ he really confronts himself.

…

Wells (and other similarly shaped structures) are a major motif in Murakami fiction as a conduit between the conscious and unconscious worlds. In Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, for instance, the protagonist’s only potential escape route from his unconscious mind is through a pond that appears to flow beneath the walls that enclose the area, presumably bringing him back to the conscious world. In Dance Dance Dance, the protagonist boards an elevator in a modern high-rise hotel, but when the doors open finds himself in a much older structure from his past. More recently, the heroine of Sputnik Sweetheart, Sumire, dreams that her long-lost mother comes back from the dead to tell her something, but is sucked into a kind of hollow tower before she can convey her message, leaving Sumire wondering whether to follow her into that world.

The well in The Wind-up Bird Chronicle becomes a central point of contention as well, and both Toru and Noboru seem to recognize the importance of controlling this important link between their two worlds. Toru’s work as a healer grows directly from his need to own and control the land on which the well is located. Achieving this at least temporarily when Nutmeg purchases the land and holds in trust for Toru, the well also serves as bait to draw Noboru out, forcing him to bargain. Eventually Noboru even concedes the possibility of returning Kumiko to Toru in exchange for giving up the well, making clear how critical control of this portal between worlds is for him.

Fortunately for Toru (and for us, his loyal cheering section), he maintains possession of the well long enough to accomplish his task, and as he moves from Room 208 to the well for the last time, the well fills with water. Even Toru, by this time, understands the importance of the water that fills the well: ‘It had been dried up, dead, for such a long time, yet now it had come back to life. Could this have some connection with what I had accomplished there? Yes, it probably did. Something might have loosened whatever it was that had been obstructing the vein of water.’ The fact that he might drown in the well as it fills with water does not seem to trouble him much; ‘I had brought this well back to life, and I would die in its rebirth. It was not a bad way to die, I told myself.’

But Toru, as we know, is rescued in the end by Cinnamon, and this leaves us with one interesting question: How will Toru maintain his own identity if his unconscious ‘other’ no longer exists? Are we to imagine that Noboru Wataya in his unconscious mind is still alive somewhere, back where he belongs? On this one point we might, perhaps, quibble with Murakami’s decision to save his hero from death at the end of the novel.

In terms of the overall quest of The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, then, the novel provides a successful conclusion. By beating his ‘other’ to death in the unconscious world, Toru has achieved his goal, and if proof is required, Murakami provides it in the restoration of the well – Toru’s own private conduit to the ‘other world’ – with the flow of water – significantly, warm water, offering the promise of new life.

…

I noted above that ‘flow that is so important a metaphor for life and fertility is also a metaphor for time, and this brings us, at last to the ‘wind-up bird’ itself. The wind-up bird is, of course, an ‘open’ symbol, like Melville’s whale, and can thus be read simultaneously in a number of ways.

Toru himself offers several suggestions within the narrative. Upon reading Cinnamon’s ‘Wind-up Bird Chronicle #8,’ for instance, he suggests that the bird is a harbinger of doom, a source of deadly fate. ‘The cry of the bird was audible only to certain special people who were guided by it toward inescapable ruin.’ In this sense, the bird takes on a god-like role, as controller of human destiny. People, according to this suggestion, are like puppets set in motion for the bird’s amusement, or, as Toru puts it, like wind-up dolls.

‘People were no more than dolls set on tabletops, the springs in their backs wound up tight, dolls set to move in ways they could not choose, moving in directions they could not choose. Nearly all within range of the wind-up bird’s cry were ruined, lost. Most of them died, plunging over the edge of the table.’

Based on this reading we might see the wind-up bird as symbolic of the power of the State itself, manipulating and using the people in ways they cannot control. Indeed, this is the essential structure of A Wild Sheep Chase, in which the Sheep, a source of unimaginable power, takes control of the weak-minded and rules human destiny through them. It is thought, in that book, to have been the source of the military genius of Genghis Khan, as well as the root of power in elements of the Japanese State during World War II.

If we choose to view the wind-up bird in this sense, then Noboru’s ‘special power’ to take control of people’s core identities is surely connected to it. As a politician, a representative of political power in Japan, Noboru’s transformation from a sloppy, socially inept college professor into a slick, yet artificial, politician could easily be attributed to some mysterious relationship with the wind-up bird.

This is a plausible reading of the wind-up bird, and could be pursued in much greater depth…But I wish to offer an alternative reading, one that takes into account the motif of flow and time. I wish to read the ‘wind-up bird’ as a metaphor for time and history.

Toru himself offers a reading of the bird in this way from the earliest part of the novel: the bird’s real function, he believes is to ‘wind the spring of our quiet little world.’ In other words, the turning of the world – and its attendant creation of ‘time’ – rests in the hands of this mystical bird, whose task is to keep time flowing forward, creating temporal distance between past and present.

But the springs, like all springs, do wind down, and must be rewound by the bird. These are the points at which the bird’s cry is heard, and also the moments of tension in the novel, when disparate worlds seem to crash into one another. The bird’s cry is heard when historical moments – past and present, present and future – slam into one another as a result of the loss of momentum in time. According to this reading, the bird is not the cause of catastrophe, then, but naturally appears in order to set the flow of time going again. This may help us to understand the prophesies that appear at various points in the book: Cinnamon’s discovery of the buried heart, prophesying the death and mutilation of his father; the various parenthetical prophesies concerning the soldiers in Manchuria, and even Honda’s prophetic warnings to Toru and Mamiya.

This also allows us to comprehend better why May Kasahara nicknames Toru ‘Mr. Wind-up Bird;’ his function, like the bird’s is to restore the ‘flow,’ reestablishing a fertile relationship between ‘self’ and ‘other.’ In this context, he and the ‘wind-up bird’ may have more in common than he realizes.”

[MY NOTE: I also wonder if the bird could be an allusion to the birds in Slaughterhouse Five – we know Murakami is an admirer of Vonnegut.]

“Like the well, filling at last with water at the end of the novel, the human ‘self’ is characterized as a vessel into which stimuli are poured like water, to be stirred in the crucible of the unconscious, processed into the memories and experiences that make us who we are. When the process is permitted to continue smoothly, according to the flow of energy back and forth between the two modes of consciousness, human identity is stable and secure.

But, as we have seen, identity does not always work so smoothly. Human identity in this novel is altogether too fragile, too vulnerable to removal, transport, or even destruction. It can be replaced by another. When Cinnamon awakens from his terrifying dream of seeing another ‘him’ sleeping in his bed, for instance, he intuitively understands that his ‘self’ has been placed into another body that looks like his own, but is not. ‘He felt as if his self had been put into a new container…There was something about this one, he felt, that just didn’t match his original self.’

At the same time, identity that has been lost can also be recreated. Creta Kano has suffered a catastrophe even greater than Cinnamon’s, and now describes herself as ‘empty,’ but she is rebuilding her identity, piece by piece. ‘I am now quite literally empty. I am just getting started, putting some contents into this empty container little by little,’ she tells Toru, for ‘Without a true self…a person cannot go on living. It is like the ground we stand on.’ Like the well that fills with water at the end, all of the victims of the Wind-up Bird Chronicle attempt to refill the empty vessels left behind after their core identities have been removed. Some, like Creta Kano and Cinnamon, are partially successful; others, such as Mamiya, end in dismal failure.

Whether the central quest to ‘save’ Kumiko will be successful is left uncertain as of novel’s end. Toru has reestablished contact with her by the end of the work, but we cannot say whether she will ever be able to reconstruct her identity. An educated guess might lead us to believe (or at least to hope) that Toru will recover Kumiko and, following the restoration of fertility he has achieved, that they will have a child together. ‘If Kumiko and I have a child, I’m thinking of naming it Corsica,’ he tells May Kasahara, again, returning to what Malta tells him in his dream. If my reading is correct, and if Creta Kano and Kumiko are indeed one and the same, than Malta Kano’s words are the final prophesy in this book, and a harbinger of healing and restoration.”

So…we’re come to an end of The Wind-up Bird Chronicle. My take? Great book, complex, messy (no, not everything comes together smoothly despite Murakami’s best efforts) and endlessly fascinating. It’s my second time reading it, and this time I think I have a much better handle on how it works together and how is WWII is central to the story. By “killing” Noboru Wataya, are Kumiko and Toru killing off the remains of the “force” that brought about the war?

Some questions for the group:

Any other ideas how to read/interpret the wind-up bird?

Who is Cinnamon really? Is he the force that created all the events in the story? Is it possible that everything that happens to Toru is part of a structure constructed BY Cinnamon with his computer?

Who is the “man without a face” in the unconscious hotel? He knows his way through most of the hotel but not its structure as a whole – is he Cinnamon? Is he Toru himself?

What are the other ways that things connect? I discussed in my last post Toru’s progression, but what happens when you try to break down what is true, what is one of Cinnamon’s stories what is magic what is real what is past and what is present?

And finally – does the ending satisfy? Does the book work as a cohesive whole? Since the book seems to be structured along the lines of a detective novel, does it matter that there are unresolved questions at the end?

Please…share with the group your thoughts, your take, your questions!

My next post: Tuesday, July 29th – my introduction to our next book, my favorite novel of Murakami’s (at least to date) – Kafka on the Shore.

Enjoy.